In this fifteenth post regarding my recap/review of James Dunn’s volume Neither Jew nor Greek I will attempt to summarize his 100+ page (!) research regarding how the second century Christians sources handled the oral traditions about Jesus. Needless to say, many of the finer details will have to pass in favor of a more general overview of what each writer had at their disposal, whether it be written documents, sayings committed to memory, or shorthand summaries of memorized verses. If you want the summary, scroll down to the TL;DR section.

One thing which I found interesting in this chapter was Dunn’s insistence that readers not immediately assume that just because a second century CE Christians uses Scripture (as we understand ‘Scripture’ today) that we too quickly assume that they had a document at their disposal. As we witnessed with the second century document Gospel of Thomas, the traditions of Jesus continued to be passed on orally even after the writing of the four NT Gospels. Could it be that even second century Christians continued to value oral transmissions of Jesus traditions? At what point did the written documents (Gospels) take priority over orally transmitted data regarding Jesus? Dunn seeks to answer these questions with a massive study which includes the Apostolic Fathers, early Apologists, and Gnostic writings.

One thing which I found interesting in this chapter was Dunn’s insistence that readers not immediately assume that just because a second century CE Christians uses Scripture (as we understand ‘Scripture’ today) that we too quickly assume that they had a document at their disposal. As we witnessed with the second century document Gospel of Thomas, the traditions of Jesus continued to be passed on orally even after the writing of the four NT Gospels. Could it be that even second century Christians continued to value oral transmissions of Jesus traditions? At what point did the written documents (Gospels) take priority over orally transmitted data regarding Jesus? Dunn seeks to answer these questions with a massive study which includes the Apostolic Fathers, early Apologists, and Gnostic writings.

The Apostolic Fathers

1 Clement – Two passages in particular (13.2 and 46.8) contain quotes of Jesus’ words, both with introductions, “Remember the words of the Lord Jesus, for he said…”. After comparing the seven saying of Jesus in 13.2 Dunn notes that there is hardly any hard evidence which indicates literary dependence upon Matthew, Mark, or Luke. Rather, these sayings were collected and adapted for a particular teaching emphasis/theme. The same can be said of 46.8, where the variations of 1 Clement’s words when compared to the Greek text of the Synoptics indicates that no direct literary dependence is taking place. Rather, Clement is drawing from a range of teachings available to him to serve his paraenetic purposes (Clement never refers to a written Gospel and likely does not possess a copy of any of the four NT versions).

Ignatius – Within the seven letters of Ignatius we can observe a few allusions to Jesus material (Dunn examines six examples). Each of the examples sampled from among Ignatius’s letters are attributed to quotations from memory rather than to copying from a written text. It could be that the various quotes were from certain Jesus sayings which were circulating orally. We should, however, remember that these documents were written on the road to Ignatius’s martyrdom, and it is hardly likely that he would have had in his possession the actual copies of the four Gospels during his Roman custody.

Polycarp – Dunn focuses on Polycarp’s letter to the Philippians which introduces Jesus tradition with the formulaic “the Lord said when he taught.” Polycarp seems to have had access to the Lord’s Prayer, although the nature of this saying indicates that it would have likely been transmitted orally in liturgical settings. So when Polycarp seems to cite this prayer or parts of it) in Phil. 6.2 it seems that there is no literary dependence, per se. Chapter 7.1-2 seems to demonstrate an awareness of the Johannine corpus, but in the end it does not seem like Polycarp drew these references upon his own reading of John’s Gospel. In sum, Dunn suggests that the strong influence of Matthaean and Johannine traditions within the letters of Polycarp are most likely to be attributed to the influence of these Evangelists within Asia Minor, but not necessarily indicating that the actual literary documents were being cited.

Didache – The author of this document owes a great deal of its material to Matthew’s Gospel, as it easily observed with simply a casual reading. More specifically, Dunn notes that the Q material is particularly parallel (both in Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount and Luke’s Sermon on the Plain). The sequence of the citations, which do not follow Matthew’s own ordering, suggests a lack of close literary dependence. Some of the Jesus traditions seem to have undergone an expansion (Did. 1.4-6; cf. 1 Pet. 2:11). It is often noted that the longer baptismal formula, which includes the reference to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, is included in the Didache. Nevertheless, the nature of this saying, being one certainly used in some circle of liturgical practice, strongly suggests that it was communicated to the Didachist received it orally rather than from his reading of Matthew’s Gospel. In the end, Dunn argues that the oral Jesus traditions contained within Matthew’s Gospel were an extremely strong influence upon the author of the Didache, particularly based upon the Gospel’s overall popularity with the churches of the eastern Mediterranean.

Barnabas – Sadly, the Epistle of Barnabas cites very few traditions of Jesus. In Barn. 5.9 there is a reference to Jesus not coming “to call the righteous but the sinners,” but Dunn notes that this saying can be observed within a wider spectrum (cf. Gal. 2:14-17 and 1 Tim. 1:15). Chapter 5.12 cites the “When they smite their own shepherd, then the sheep of the flock will perish,” which sounds like Matt. 26:31 and Mark 14:27. However, both of these Evangelists are themselves citing Zech. 13:7, and Dunn suggests that this is most likely what the author of Barnabas is doing. Similarly, Psa. 110:1 is alluded to, but the frequency in which early Christians utilized this passage (being the most cited OT passage in the NT) indicates the likelihood that it was known orally in wider Christian circles. Overall, Dunn summarizes his findings by stating that the story of Jesus’ passion were widely told and retold, and these best explain the Jesus traditions encountered within Barnabas (rather than his dependence upon literary documents).

The Shepherd of Hermas – Somewhat disappointing, The Shepherd makes no explicit reference to any of the NT Gospels (or any of Paul’s letters for that matter). Within the Similitudes and the Mandates are some allusions to Jesus traditions, but Dunn suggests that these are best explained as examples of how language and themes have become a part of the regular vocabulary and motifs used by early Christian teachers.

2 Clement – This document, written by a pseudonymous author, regularly begins citations of Jesus traditions with introductory phrases like, “The scripture says,” or, “The Lord says.” Dunn analyzes nine references to Jesus material found within the Synoptic Gospels and notes that there are significant variances which warrant an assessment of the author utilizing orally transmitted sayings and teachings. 2 Clement 12.2 even cites the Gospel of Thomas 22.1-5, although this too is attributed to an oral allusion rather than to literary dependence. Dunn wonders if the pseudonymous author is attempting to rescue (what he felt were) the saying in Thomas from its Gnostic context and interpretation. Dunn notes that 2 Clement 9:5, which argues that Jesus was first spirit and then became flesh, is hardly a citation from John 1:14 in literary form. Rather, it seems that it was the author’s own reflection on what that passage said to him.

Papias – Papias is an interesting subject. His writings only survive in fragments recorded by Eusebius. However, Dunn was able to draw out of the Papias material a lot of interesting observations which helped his initial inquiry. First of all, Papias mentions oral traditions of Jesus which continued to circulate, calling them “unwritten tradition.” Secondly, Papias himself mentions that “he received the words of the apostles from those who had associated with them,” indicating a three-stage link of apostles, companions, and then Papias. Thirdly, Dunn notes the subtle but important difference between how Papias mentions that the apostles “said” (aorist active) and how Ariston and the elder John “were saying” (present active). This indicates that Papias never met or heard the apostles. Fourthly, Papias names seven of the twelve apostles as those from whom authentic Jesus material had been transmitted (including the lesser-known Andrew, Philip, and Thomas). Fifthly, Papias distinguishes between “what came from the books” and “what came from a living and abiding voice.” Dunn also notes that Papias was surely aware of other teachings, i.e., competitors to what he felt were authentic teachings of Jesus. After surveying all of the data, Dunn suggests that Papias was aware of all four of the NT Gospels and regarded them as providing authentic records of Jesus’ teachings.

The Apologists

Aristides – Aristides’s apology to the emperor Hadrian alludes to the “writings of the Christians” (16.1), but sadly says very little of value for Dunn’s inquiry. Echoes of Matt. 13:44 and John 19:37 can be discerned from the document, but these are likely due to the influence of Matthew and John rather than to literary dependence.

Justin Martyr – Justin clearly is aware of the Gospel in written form. All three of the Synoptic Gospels are clearly alluded to, with strong ties with Matthew and Luke in particular. Of interesting note, Dunn observes that Justin nowhere quotes explicitly from the Gospel of John. One of the most interesting allusions appears in 1 Apol. 61.4 which draws upon John 3:3, 5. Here Justin writes, “Unless you have been born again you shall by no means enter the kingdom of heaven,” while John’s Gospel uses “kingdom of God” instead. This seems to indicate a loose level of quoting significant Jesus material, rather than positing that John 3:3 possesses a significant textual variant upon which Justin is citing.

Tatian – In his Address to the Greeks Tatian alludes to a few of the Jesus traditions. He seems to be aware of passages from John’s Gospel and perhaps a small allusion to Matt. 13:44. More helpful is Tatian’s Diatessaron which weaves together all four of the NT Gospels accounts (including material from John chapter 21). This document indicates that by the middle of the second century (in Rome at least) the four Gospels were well-known and understood as authoritative documents for faith and practice. Obviously, Tatian demonstrates literary dependence upon all four documents.

Athenagoras – Dunn cites four examples within the Plea to demonstrate that Athenagoras drew upon the Synoptic Gospels in a manner which indicates direct literary influence. Furthermore, the treatise On the Resurrection bears resemblance of much of the christological teachings contained within the Gospel of John. These, however, are not quotations but rather strongly influential allusions from oral teachings. Dunn makes a comment noting how this apologist was regarded as a mainstream teacher of second-century Christianity (despite not possessing an actual copy of John’s Gospel).

Theophilus of Antioch – Theophilus clearly demonstrates literary dependence upon Matthew and John. In particular, he introduces teachings of Jesus about ‘chastity’ and ‘responses to persecution’ with introductions such as, “the voice of the Gospel,” and, “the Gospel says…” etc. Of further interest is Jerome’s report that Theophilus composed his own version of a harmony of the Gospels, described as “one work…the words of the four Evangelists” (Ep. 121.6.15). This indicates that he possessed all four Gospels and regarded only those four as authoritative.

Melito of Sardis – Unfortunately, Melito does not say much in regard to the teachings of Jesus. His few faint allusions to Matthew, Mark, and John are best described as shared teachings rather than evidence of any sort of literary dependence. Melito is, however, aware of the passion narrative of Jesus and a few of Jesus’ miracles.

Irenaeus – By the end of the second century CE there seems to be a significant shift with the works of Irenaeus. He committed himself to the four NT Gospels and no other Gospel. His exegesis indicates his awareness and careful study of the documents, strongly suggesting that he possessed them personally. He not only quotes them but expounds upon them (particularly Matthew’s Gospel). He furthermore indicates how the Valentinians “gather their views from other sources than the scriptures” (Adv. Haer. 1.8.1).

In his summary of the Apologists, Dunn notes the trend from oral teachings of Jesus to written sources possessed by the writers. He also notes that the Gospel of Thomas plays little to no role in their theologies. There seemed to be a stress upon four numerical Gospels as both the correct number of documents for Jesus tradition and as authoritative ‘scripture’ for the Church’s use.

Gnostic Gospels

The Dialogue of the Savior – This Gnostic work shows no familiarity with the Synoptic Gospels. It does, however, draw heavily upon the Gospel and John and the Gospel of Thomas. The influence from Thomas, which is considerable, shift the line of thought into a Gnostic-like narrative. Interestingly, Dial. Sav. 57 regards 1 Cor. 2:9 as a saying of Jesus (just as Gospel of Thomas 17 does). This document represents a shift away from the earlier traditions of Jesus (or at least a lack of awareness of them).

Apocryphon of James – This document is interesting. It shows influence from all four Gospels and even the Epistle to the Galatians. None of these allusions can be demonstrated to prove that there was any literary dependence however. They are too remote and are not even cited with any sense of authoritativeness. It does regard itself as a “secret book” which claims to remember what Jesus taught during the 550 days (!) of his resurrection appearances (Apoc. Ja. 1.8-10; 2.8-21). In effect, the unknown writer is admitting openly that his presentation was remote, arguing that its teaching was given secretly to James and Peter (1.10-12).

Gospel of Philip – This document is best characterized as an anthology of miscellaneous sayings, similar to Thomas. It presents an awareness of all four Gospels, 1 Corinthians, Ephesians, and 1 Peter. However, these documents are used to further Philip’s own theological agenda, which is Gnostic in character. In fact, Dunn observes a Valentinian form of Gnosticism taught by the Gospel of Philip. This document fails to value the teachings of Jesus as important and does not climax in the death/resurrection of Jesus. Both Dunn and I regard these qualities as means to dismiss this document as a correct representative of the ‘Gospel’ label of genre.

Gospel of Truth – This document echoes the Christian gospel message and even draws upon earlier Jesus traditions of Matthew, Luke, and John. However, the repeated emphasis on knowledge, its talk about enlightening those within a fog, the intended recipients as described as lost in ignorance, and the desire to bring them to a resting-place with the Father all point to a Gnostic theology foreign to the earliest Gospels. In other words, the ‘good news’ presented in the Gospel of Truth is provided as an answer to a “very different analysis of the human condition…”

Gospel of Mary – The embarrassment that a female was the first to witness the resurrected Jesus in John’s Gospel (20:1-18) seems to be the driving force in this document. It attributes the salvation process to this Mary rather than to Andrew and Peter (representatives of early Jerusalem leadership). Gospel of Mary shows knowledge of Jesus traditions within all four Gospels, but its aim is to draw attention away from the ‘good news’ as described by patriarchal mainstream Christian teachings.

Gospel of the Savior – This document demonstrates awareness of Matthew, John, and even the Book of Revelation. In regard to the inquiry regarding the transmission of Jesus traditions this document is quite unhelpful. Its primary aim seems to be the personification of the cross, to which Jesus speaks (“O cross”) with similarities to the Gospel of Peter.

Gospel of Judas – This highly Gnostic work offers little value for the development and transmission of oral Jesus traditions. The Synoptic account of Peter’s confession is alluded to, but is mocked with a parody (making the disciples make the confession instead). The document shows evidence of an elaborate cosmology exhibited from a later stage of Gnostic theology which reveal the true nature to the recipients of Jesus’ teachings (as observed in Gospel of Thomas and Dialogue of the Savior).

Secret Mark – Although the debate continues in regard to the date and authenticity of this document, it does demonstrate an awareness of the Gospel of Mark and the Gospel of John. However, it is of little value for Dunn’s inquiry because it provides little information about the Jesus traditions.

TL;DR

- The Jesus traditions continued to be transmitted orally during the second century, despite the fact that all four Gospels were written in the first century. The written Gospels did not bring the oral Jesus traditions to an end.

- The traditions of Matthew’s and John’s Gospels were particularly valued in catechetical, liturgical, and apologetic settings (even without the actual literary documents present).

- By the end of the second century CE the oral traditions of Jesus became used less often and were replaced by the testimony of the four written Gospels.

- The Gnostic documents relied less on the earliest Jesus traditions and instead valued other sources for their teachings (i.e. Thomas).

- Irenaeus regarded the four Gospels as both authoritative and the standards against which other perversions of authentic Jesus traditions were to be measured. Any and all other teachings were deemed as threats (or odd curiosities) to the majority of Christians.

Thanks for reading this far. Please subscribe for further updates and share if you enjoyed this post!

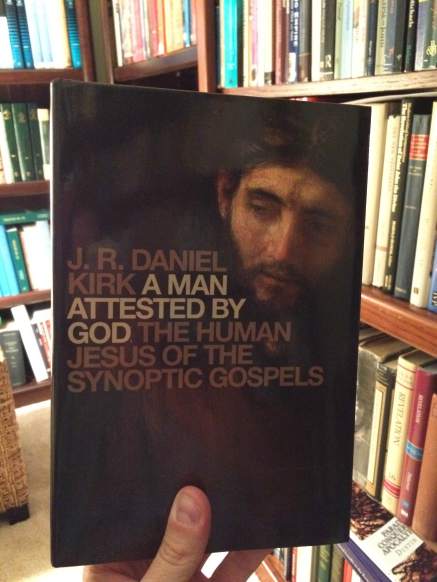

newest book, A Man Attested by God: The Human Jesus of the Synoptic Gospels. Overall his thesis is proving to be extremely persuasive as well as a welcome addition to the many scholarly voices on Christology these days. Today I will discuss the section entitled “Son of God in Matthew,” which is the final section in the second chapter. As per my custom, I will summarize and review Kirk’s arguments in bullet points while adding a few comments and observations of my own in italics.

newest book, A Man Attested by God: The Human Jesus of the Synoptic Gospels. Overall his thesis is proving to be extremely persuasive as well as a welcome addition to the many scholarly voices on Christology these days. Today I will discuss the section entitled “Son of God in Matthew,” which is the final section in the second chapter. As per my custom, I will summarize and review Kirk’s arguments in bullet points while adding a few comments and observations of my own in italics.

Happy Labor Day and welcome to my seventh post containing my reviews and thoughts on Daniel Kirk’s newest volume,

Happy Labor Day and welcome to my seventh post containing my reviews and thoughts on Daniel Kirk’s newest volume,  This is post number six in my ongoing series containing my reviews and thoughts on Daniel Kirk’s newest volume,

This is post number six in my ongoing series containing my reviews and thoughts on Daniel Kirk’s newest volume,  the problem nations by moving from chaotic animals back to the idealized role of humanity in Genesis 1 (where humans rule over the animals). Just as the beasts represents nations, so too does the Son of Man represent Israel as a nation/people, albeit as a single figure. Much discussion and conversation with John Collins regarding the interpretation of the “holy ones” (angels or humans). Here Kirk sees the Son of Man as one enthroned alongside God in heaven and receiving universal worship, although still existing as a human figure (rather than angelic). He also notes that the Son of Man, having suffered persecution from the “little horn” in Daniel 7, is vindicated precisely as a suffering figure. It will be interesting to see where Kirk ends up going with this line of argumentation, as I can already see the dialogue with Jesus and the priest in Mark 14 as a strong candidate for this evidence.

the problem nations by moving from chaotic animals back to the idealized role of humanity in Genesis 1 (where humans rule over the animals). Just as the beasts represents nations, so too does the Son of Man represent Israel as a nation/people, albeit as a single figure. Much discussion and conversation with John Collins regarding the interpretation of the “holy ones” (angels or humans). Here Kirk sees the Son of Man as one enthroned alongside God in heaven and receiving universal worship, although still existing as a human figure (rather than angelic). He also notes that the Son of Man, having suffered persecution from the “little horn” in Daniel 7, is vindicated precisely as a suffering figure. It will be interesting to see where Kirk ends up going with this line of argumentation, as I can already see the dialogue with Jesus and the priest in Mark 14 as a strong candidate for this evidence.  the priestly image in Genesis 14 and the kingly role in Psalm 110. Since King David and his sons, on rare occasions, functioned as both kings and priests (2 Sam 8:18) this allows Psalm 110 to promote a human lord as the idealized priestly king. Furthermore, Psa 110:1 envisages this human lord as exalted to God’s right hand, followed by an appointment of priesthood forever (110:4). Yet this figure is distinct from YHWH in both Genesis 14 and Psalm 110.

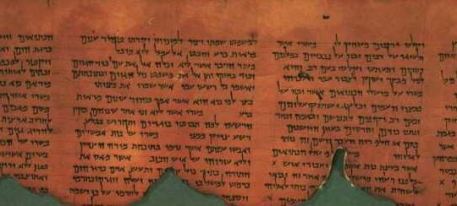

the priestly image in Genesis 14 and the kingly role in Psalm 110. Since King David and his sons, on rare occasions, functioned as both kings and priests (2 Sam 8:18) this allows Psalm 110 to promote a human lord as the idealized priestly king. Furthermore, Psa 110:1 envisages this human lord as exalted to God’s right hand, followed by an appointment of priesthood forever (110:4). Yet this figure is distinct from YHWH in both Genesis 14 and Psalm 110. two times in the DSS the authors replaced the divine name (YHWH) with the name of a human priest (just as the NT does with Jesus in Rom 10:13 and Acts 2:21). In particular, the moreh hatzadik (“Teacher of Righteousness”) in the Habakkuk Pesher puts the reference to the teacher in for the divine name. This also occurs in 4Q167 where the “last priest” replaces the first person reference to Yahweh’s “I” in Hosea 5:14. This observation is hugely significant, noting that the NT authors were not going rogue in their high claims made of Jesus. They were only doing what other Jews were practicing before them.

two times in the DSS the authors replaced the divine name (YHWH) with the name of a human priest (just as the NT does with Jesus in Rom 10:13 and Acts 2:21). In particular, the moreh hatzadik (“Teacher of Righteousness”) in the Habakkuk Pesher puts the reference to the teacher in for the divine name. This also occurs in 4Q167 where the “last priest” replaces the first person reference to Yahweh’s “I” in Hosea 5:14. This observation is hugely significant, noting that the NT authors were not going rogue in their high claims made of Jesus. They were only doing what other Jews were practicing before them.  In this third post wherein I provide my review and thoughts on Daniel Kirk’s

In this third post wherein I provide my review and thoughts on Daniel Kirk’s  God’s son on earth per 2 Sam 7:14 (cf. Psa 2:7). 2 Samuel’s reworking in 1 Chronicles 17:11-14 signifies that the Davidic kingdom is also the kingdom of God, indicating that the human ruler is the one through whom God is/will be enacting his sovereignty.

God’s son on earth per 2 Sam 7:14 (cf. Psa 2:7). 2 Samuel’s reworking in 1 Chronicles 17:11-14 signifies that the Davidic kingdom is also the kingdom of God, indicating that the human ruler is the one through whom God is/will be enacting his sovereignty. worshiped, being the recipients of a single verb in 1 Chron 29:20. In 1 Chron 29:23 Solomon sits on the throne of Yahweh, indicating that Yahweh has invested his personal rule and throne upon the earth so that the human king can function as his embodied representative. The Israelite king, therefore, is the visible presence of Yahweh.

worshiped, being the recipients of a single verb in 1 Chron 29:20. In 1 Chron 29:23 Solomon sits on the throne of Yahweh, indicating that Yahweh has invested his personal rule and throne upon the earth so that the human king can function as his embodied representative. The Israelite king, therefore, is the visible presence of Yahweh. plethora of interpretations by scholars (about which Kirk shows awareness), notes how the God’s anointed one will be obeyed/listened to by the heavens and the earth. This recalls the primordial Adam image who functioned as the crowning achievement of the original creation, ruling over everything God had created.

plethora of interpretations by scholars (about which Kirk shows awareness), notes how the God’s anointed one will be obeyed/listened to by the heavens and the earth. This recalls the primordial Adam image who functioned as the crowning achievement of the original creation, ruling over everything God had created.  an actual living representation who points creation to the true God in heaven. Adam is made in God’s image and likeness and rules as God’s viceroy. Rulership over creation is a divine prerogative given to Adam. This makes Adam an idealized human figure. I would like to add to Kirk’s analysis that the P source of Genesis 2 tells of God letting Adam name the individual animals (another divine prerogative as observed in P’s record of God himself naming the day, night, sun, moon, etc.).

an actual living representation who points creation to the true God in heaven. Adam is made in God’s image and likeness and rules as God’s viceroy. Rulership over creation is a divine prerogative given to Adam. This makes Adam an idealized human figure. I would like to add to Kirk’s analysis that the P source of Genesis 2 tells of God letting Adam name the individual animals (another divine prerogative as observed in P’s record of God himself naming the day, night, sun, moon, etc.).  throne unto Moses. As Moses looks over the created order, some of the stars bow down before him. If these stars are a reference to angels them Kirk has a good argument against Bauckham and even Fletcher-Louis regarding how humans can be given roles which are regularly reserved for God alone. This reminds me of the Apocalypse of John in the NT where human beings are to be worshiped but angels refuse the very same action.

throne unto Moses. As Moses looks over the created order, some of the stars bow down before him. If these stars are a reference to angels them Kirk has a good argument against Bauckham and even Fletcher-Louis regarding how humans can be given roles which are regularly reserved for God alone. This reminds me of the Apocalypse of John in the NT where human beings are to be worshiped but angels refuse the very same action.  Elijah the Tishbite as controlling aspects of nature in ways which are generally reserved for God alone. In fact, the awesome episode upon Mount Carmel in 1 Kings 17 indicates that it is the human Elijah, and not Baal the storm god, who controls the storms. Yet no one honestly thinks that Elijah is divine. Rather, everyone knows that he is a faithful prophet of God empowered to do miracles and wonders. Kirk notes the many ways in which the deuteronomist sees Elijah as the parallel figure to Moses, noting where both persons do the same miracles and feats. If Moses was an idealized human figure then certainly Elijah is depicted in Scripture to be similarly understood!

Elijah the Tishbite as controlling aspects of nature in ways which are generally reserved for God alone. In fact, the awesome episode upon Mount Carmel in 1 Kings 17 indicates that it is the human Elijah, and not Baal the storm god, who controls the storms. Yet no one honestly thinks that Elijah is divine. Rather, everyone knows that he is a faithful prophet of God empowered to do miracles and wonders. Kirk notes the many ways in which the deuteronomist sees Elijah as the parallel figure to Moses, noting where both persons do the same miracles and feats. If Moses was an idealized human figure then certainly Elijah is depicted in Scripture to be similarly understood! In the opening chapter, which is really the important introduction to the book, Kirk cites Acts 2:22 as a sufficient declaration of Jesus’ identity articulated in the three Synoptic Gospels. Since Acts is the second volume of Luke’s two contributions to the New Testament, citing Peter’s christology which regards Jesus as “a man attested to you by God through miracles, wonders, and signs” makes sense. Kirk begins by clearly defining his term “idealized human figure” as referring to a non-angelic, non-preexistent human being who plays a unique role in representing God unto creation (or vice versa). Kirk furthermore suggests that this terminology is a reasonable third alternative to the more commonly (at least in modern christological discourse) expressed terms of a “low Christology” and a “high Christology.” So far so good.

In the opening chapter, which is really the important introduction to the book, Kirk cites Acts 2:22 as a sufficient declaration of Jesus’ identity articulated in the three Synoptic Gospels. Since Acts is the second volume of Luke’s two contributions to the New Testament, citing Peter’s christology which regards Jesus as “a man attested to you by God through miracles, wonders, and signs” makes sense. Kirk begins by clearly defining his term “idealized human figure” as referring to a non-angelic, non-preexistent human being who plays a unique role in representing God unto creation (or vice versa). Kirk furthermore suggests that this terminology is a reasonable third alternative to the more commonly (at least in modern christological discourse) expressed terms of a “low Christology” and a “high Christology.” So far so good. primary arguments of the modern contributors of early high Christology and indicates their weaknesses (or what these scholars fail to state). Richard Bauckham, for example, argues that Jesus is “identified with God,” but Bauckham does not come out and say that Jesus is identified as God. Another example is made out of Larry Hurtado who regards the cultic worship given to the exalted Jesus as appropriate for the Creator, but Hurtado refuses to come out and say that Jesus is in fact the Creator. Similarly, Darrell Bock regards Jesus as one possessing “more than human authority,” but never fleshes out what this exalted status actually is or entails. I personally have noticed that these scholars (and others articulating an early high Christology) never come out and openly say that the NT authors unambiguously teach Nicene or Chalcedonian understandings of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. They regularly throw around the word “divine” in regard to Jesus’ identity, almost always

primary arguments of the modern contributors of early high Christology and indicates their weaknesses (or what these scholars fail to state). Richard Bauckham, for example, argues that Jesus is “identified with God,” but Bauckham does not come out and say that Jesus is identified as God. Another example is made out of Larry Hurtado who regards the cultic worship given to the exalted Jesus as appropriate for the Creator, but Hurtado refuses to come out and say that Jesus is in fact the Creator. Similarly, Darrell Bock regards Jesus as one possessing “more than human authority,” but never fleshes out what this exalted status actually is or entails. I personally have noticed that these scholars (and others articulating an early high Christology) never come out and openly say that the NT authors unambiguously teach Nicene or Chalcedonian understandings of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. They regularly throw around the word “divine” in regard to Jesus’ identity, almost always

One thing which I found interesting in this chapter was Dunn’s insistence that readers not immediately assume that just because a second century CE Christians uses Scripture (as we understand ‘Scripture’ today) that we too quickly assume that they had a document at their disposal. As we witnessed with the second century document Gospel of Thomas, the traditions of Jesus continued to be passed on orally even after the writing of the four NT Gospels. Could it be that even second century Christians continued to value oral transmissions of Jesus traditions? At what point did the written documents (Gospels) take priority over orally transmitted data regarding Jesus? Dunn seeks to answer these questions with a massive study which includes the Apostolic Fathers, early Apologists, and Gnostic writings.

One thing which I found interesting in this chapter was Dunn’s insistence that readers not immediately assume that just because a second century CE Christians uses Scripture (as we understand ‘Scripture’ today) that we too quickly assume that they had a document at their disposal. As we witnessed with the second century document Gospel of Thomas, the traditions of Jesus continued to be passed on orally even after the writing of the four NT Gospels. Could it be that even second century Christians continued to value oral transmissions of Jesus traditions? At what point did the written documents (Gospels) take priority over orally transmitted data regarding Jesus? Dunn seeks to answer these questions with a massive study which includes the Apostolic Fathers, early Apologists, and Gnostic writings. Just to bring everyone up to speed, Thomas was a document uncovered with the Nag Hammadi cache of Gnostic works in 1945. Thomas in particular contains 114 saying of Jesus, gathered in a seemingly random order. Within the document there is no overarching story like the four NT Gospels, no discussion of miracles/healings, no passion narrative, and no reference to Jesus’ resurrection. Some of the most extreme scholars have posited that Thomas is to be dated earlier than the Synoptics, but this theory has not won over many within the guild.

Just to bring everyone up to speed, Thomas was a document uncovered with the Nag Hammadi cache of Gnostic works in 1945. Thomas in particular contains 114 saying of Jesus, gathered in a seemingly random order. Within the document there is no overarching story like the four NT Gospels, no discussion of miracles/healings, no passion narrative, and no reference to Jesus’ resurrection. Some of the most extreme scholars have posited that Thomas is to be dated earlier than the Synoptics, but this theory has not won over many within the guild.