Fourteen posts on Neither Jew nor Greek? Great googly moogly. Actually, I have been receiving a lot of positive feedback from readers and critics alike. In this post I will summarize/recap the arguments of James Dunn regarding the so-called Gospel of Thomas found within section 43.2, which followed his lengthy treatment on the Jesus traditions in the Gospel of John.

Just to bring everyone up to speed, Thomas was a document uncovered with the Nag Hammadi cache of Gnostic works in 1945. Thomas in particular contains 114 saying of Jesus, gathered in a seemingly random order. Within the document there is no overarching story like the four NT Gospels, no discussion of miracles/healings, no passion narrative, and no reference to Jesus’ resurrection. Some of the most extreme scholars have posited that Thomas is to be dated earlier than the Synoptics, but this theory has not won over many within the guild.

Just to bring everyone up to speed, Thomas was a document uncovered with the Nag Hammadi cache of Gnostic works in 1945. Thomas in particular contains 114 saying of Jesus, gathered in a seemingly random order. Within the document there is no overarching story like the four NT Gospels, no discussion of miracles/healings, no passion narrative, and no reference to Jesus’ resurrection. Some of the most extreme scholars have posited that Thomas is to be dated earlier than the Synoptics, but this theory has not won over many within the guild.

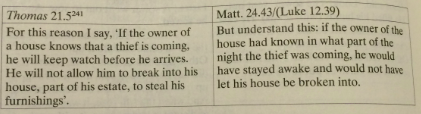

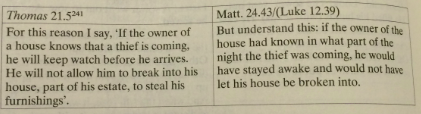

Dunn begins by noting that some of the sayings (logia) within Thomas sound a lot like the sayings located within Matthew, Mark, and Luke. In fact, it is fascinating that John, which sounds so different from the Synoptics, made it into the NT canon while Thomas, which parallels some of the Synoptic traditions of Jesus, was not included. Dunn turns to answer the question as to whether or not Thomas possesses literary dependence upon one of the previous documents (even the Q document is included into the inquiry). Here is some of the data collected from the book:

Based upon these three examples (Dunn provides seventeen total) it seems that Thomas sounds an awful lot like the Synoptic sayings of Jesus. It even appears that the closeness rivals the approximate similarities between the three different Synoptic Gospels, where Matthew and Luke drew upon Mark and redacted the sayings for their own literary and theological purposes. However, Dunn argues (against S. Gathercole and M. Goodacre) that the variations between Thomas and the Synoptics is best explained as variations of “diverse oral performances of what is basically the same tradition.” He counts 56.2% of the Thomas material as actually paralleling Synoptic traditions. Most of these parallels come from material in Matthew and Luke, suggesting that it was the Q material which strongly influenced the writer of Thomas.

On the flip side, if 56.2 % of the words in Thomas parallel the Synoptic material then 43.8% of the material sounds nothing like that Jesus exhibited in our earliest accounts. Dunn does observe a handful (eleven) of parallels with John’s Gospel, but in the end he notes that there is no evidence of literary dependence in these examples. Many of the ‘other’ sayings in Thomas deal with Jewish concerns (particularly logia 27.2; 43.2; 52.1-2; 53; 60). There is even a striking reference to James the Just in logia 12, where it notes that “heaven and earth came into existence” for his sake!

In regard to christology in Thomas it seems that Jesus secretly tells Thomas (rather than Peter the leader) that he shares the divine name (logia 13). This statement seems to be marginalizing the leadership and influence of the Petrine traditions (and documents) in favor of those within the ‘Thomas’ collection. Further statements indicate that Jesus is revered in this document not because of his death and resurrection but because he represents the Father completely. On the issue of salvation Thomas regards the realization of one’s true nature as the true redeeming act rather than a change of status involving repentance or accepting Jesus’ gospel of the kingdom of God. In fact, the overall message one gets from reading Thomas is that the good news is that Jesus descended from the Father’s kingdom to bring secret wisdom which reveals one’s true inner being, and upon acknowledging that ‘truth’ one can ensure a return to that kingdom. This may or may not be understood as a Gnostic teaching, but since it is difficult to summarize Gnosticism based on the many (sometimes conflicting) tenets exhibited in their writings this has caused some scholars to abandon the ‘Thomas = Gnostic’ label. Dunn, however, states that,

In regard to christology in Thomas it seems that Jesus secretly tells Thomas (rather than Peter the leader) that he shares the divine name (logia 13). This statement seems to be marginalizing the leadership and influence of the Petrine traditions (and documents) in favor of those within the ‘Thomas’ collection. Further statements indicate that Jesus is revered in this document not because of his death and resurrection but because he represents the Father completely. On the issue of salvation Thomas regards the realization of one’s true nature as the true redeeming act rather than a change of status involving repentance or accepting Jesus’ gospel of the kingdom of God. In fact, the overall message one gets from reading Thomas is that the good news is that Jesus descended from the Father’s kingdom to bring secret wisdom which reveals one’s true inner being, and upon acknowledging that ‘truth’ one can ensure a return to that kingdom. This may or may not be understood as a Gnostic teaching, but since it is difficult to summarize Gnosticism based on the many (sometimes conflicting) tenets exhibited in their writings this has caused some scholars to abandon the ‘Thomas = Gnostic’ label. Dunn, however, states that,

if ‘Gnostic’ can properly be used for a widespread spirituality which assumed a basic dualism between spirit and matter, which felt itself to be not at home in and at odds with the world, and which looked for an answer which resolved the paradox of human existence…then Thomas can be described as ‘Gnostic’.

What do you think of Dunn’s analysis of Thomas? Let me know in the comments below. And be sure to subscribe for further updates!

Just to bring everyone up to speed, Thomas was a document uncovered with the Nag Hammadi cache of Gnostic works in 1945. Thomas in particular contains 114 saying of Jesus, gathered in a seemingly random order. Within the document there is no overarching story like the four NT Gospels, no discussion of miracles/healings, no passion narrative, and no reference to Jesus’ resurrection. Some of the most extreme scholars have posited that Thomas is to be dated earlier than the Synoptics, but this theory has not won over many within the guild.

Just to bring everyone up to speed, Thomas was a document uncovered with the Nag Hammadi cache of Gnostic works in 1945. Thomas in particular contains 114 saying of Jesus, gathered in a seemingly random order. Within the document there is no overarching story like the four NT Gospels, no discussion of miracles/healings, no passion narrative, and no reference to Jesus’ resurrection. Some of the most extreme scholars have posited that Thomas is to be dated earlier than the Synoptics, but this theory has not won over many within the guild.