This is part of a short lecture I did on interpreting Genesis 1 and Genesis 2 in light of their contemporary ANE cosmological parallels.

This is part of a short lecture I did on interpreting Genesis 1 and Genesis 2 in light of their contemporary ANE cosmological parallels.

This is the eleventh segment of my recap/review of Dunn’s newest volume Neither Jew nor Greek. Having been distracted with responding to some of the early reviews of my own new book in addition to having to grade final exams/submit grades has placed myblogging on the back burner for awhile, so I apologize about the delays in regard to this ongoing series.

I have chosen to recap much larger sections of the book (otherwise this will be a two year endeavor). In this segment I will cover chapter forty-one, which is entitled ‘From gospel to Gospel.’ Dunn begins by reviewing the conclusions established in the first volume of these three-part series, Jesus Remembered. In particular, Dunn notes how it was the impact that Jesus left upon his earliest followers which is the oft-neglected piece of data in explaining the origins of early Christianity. He notes that gospel message preached by the apostles eventually transitioned into the creation and composition of Gospels, i.e., the literary documents recounting the life, teachings, deed, and passion of Jesus Christ.

I have chosen to recap much larger sections of the book (otherwise this will be a two year endeavor). In this segment I will cover chapter forty-one, which is entitled ‘From gospel to Gospel.’ Dunn begins by reviewing the conclusions established in the first volume of these three-part series, Jesus Remembered. In particular, Dunn notes how it was the impact that Jesus left upon his earliest followers which is the oft-neglected piece of data in explaining the origins of early Christianity. He notes that gospel message preached by the apostles eventually transitioned into the creation and composition of Gospels, i.e., the literary documents recounting the life, teachings, deed, and passion of Jesus Christ.

Dunn observes that the origin of the noun euangelion was derived from the LXX of Isa. 52:7 and 61:1. Paul himself draws upon Isa. 52:7 in Rom. 10.15, and additionally uses the noun to refer to Jesus’ Davidic descent (Rom. 1:1-3; cf. 2 Tim. 2:8), his glory (2 Cor. 4:4), and his death and resurrection. Other evidence, such as Luke’s insistence that Isaiah 61 was used by Jesus to describe his own mission and the natural question which would be posed by those baptized into Christ strongly suggests that the life, teachings, and deeds of Jesus would have been discussed in early Christian circles from an very early stage. Dunn argues that even Paul would have regarded certain aspects of Jesus’ life and mission as integral to the gospel message itself.

The Gospel of Mark seems to be structured around what many scholars have described as a ‘passion narrative with an extended introduction,’ as there are many pointers throughout the story which point forward to Jesus’ death and resurrection. However, Mark 1:1 indicates that the entire message contained within his document is gospel. One note by Dunn is worth citing at this point,

[t]he gospel of Jesus’ passion was the central but not only part of the Gospel of the mission of the Galilean who proclaimed and lived out his message of the kingdom of God.

Matthew and Luke both draw upon Mark for not only his content but also the structure of a passion narrative with an extended introduction. Within the communities associated with Matthew and Luke it seems that Jesus’ teachings was valued as itself ‘gospel’ (and part of their Gospel). Furthermore, the incorporation of Q demonstrates that these teachings of Jesus were valued to the point of assimilating them into the structure already established by Mark (and his depiction of the gospel).

John, which shows no dependence upon any of its Synoptic counterparts, nevertheless appears as a similar passion narrative with an extended introduction. Furthermore, John uses pointers within his narrative to look forward and anticipate Jesus’ passion. Dunn notes that John could have placed the emphasis on aspects such as Jesus’ ability to reveal God and the mysteries of heaven or Jesus bringing the secret meaning of human existence. Others took that approach to John, but he himself chose to stress primarily the execution and resurrection of Jesus (and regularly uses the term “glory” to denotes these two emphases.

By the second century, Justin Martyr and others had already begun to regard the term ‘Gospel’ with the four canonical documents. With this understanding, Justin would be strongly suspicious of any other claims to the title ‘Gospel’ which did not line up with what Mark and co. had established. How this played out in the early church’s rejection of other documents is a question with Dunn plans on returning to address later in the book.

Be sure to subscribe for further updates and share if you enjoyed his post! Have a great day.

This data might be old hat to some, but I finally got around to placing Gen. 1:1-2:3 in its context as an ancient cosmology in order to ascertain any similarities or differences it has with other creation accounts within the Ancient Near East. Hopefully, this study helps you allow Genesis 1 to function as intended, as a theological document (rather than a scientific document).

This data might be old hat to some, but I finally got around to placing Gen. 1:1-2:3 in its context as an ancient cosmology in order to ascertain any similarities or differences it has with other creation accounts within the Ancient Near East. Hopefully, this study helps you allow Genesis 1 to function as intended, as a theological document (rather than a scientific document).

The Separation of Heaven and Earth

The Subjugation of Sea Monster Dragon (tannim)

What enemy has arisen against Baal,

What foe against the rider of clouds?

Have I not crushed the lover of El, ‘Sea’?

Have I not destroyed El’s flood Rabbim?

Have I not muzzled the Dragon (tannim)?

I indeed did crush the crooked serpent (lotan, cf. leviathan)

The foul-fanged, the seven-headed.[2]

“God created the great sea monsters (tannim) and every living creature that moves” (Gen. 1:21).

The Function of the Sun, Moon, and Stars

Creation by a Word

The Function of Human Beings

Out of his blood they fashioned humankind.

Ea imposed the service and let free the gods.

After Ea, the wise created humankind,

They imposed upon them the service of the gods—

That work was beyond comprehension[5]

In conclusion, it seems that while the ancient cosmology described in Gen. 1:1-2:3 shares much in common with other creation accounts in the Ancient Near East, it is in the matters where they differ that set it apart and bring it distinction within Israelite (and Christian) theology. Genesis, like any other ancient document, needs to be appropriately placed in its ancient context in order to be both suitably appreciated and responsibly interpreted.

[1] ANET 67.

[2] ANET 137, with some minor modifications.

[3] ANET 68, where the Anunnaki are considered to be the celestial star deities.

[4] The Atrahasis Epic can be seen here: http://webserv.jcu.edu/bible/200/Readings/Atrahasis.htm.

[5] ANET 68, slightly modernized.

I would argue that I sure have been guilty of this.

Let me make my case here. Please read closely. I think that identifying the correct genre within the various books of the Bible is absolutely critical to understanding what the author tried to convey. Some may not be familiar with the word ‘genre’, for which I supply what dictionary.com has to offer:

-of or pertaining to a distinctive literary type.

The Bible has an abundance of different genres. Here are a few off the top of my head: prophetic, narrative, wisdom, parable, apocalyptic, poetry, covenants, etc. Each of these pieces of literature has certain restrictions and, more importantly, have certain expectations for readers. It would be wrong for me to read a poetry passage the same way I would read a narrative section of Scripture. One of the main problems raised by believers in my circles is that most of the Christian world fails to see that John 1:1-18 is precisely poetry, and thereby misses out on a dynamic which the author is trying to extend to readers. Another example of confusion common to Bible readers is a reading a Genesis chs. 1-2 as science instead of theological cosmology. More could be said on these two examples, but I’ll press on for the time being.

Readers of a newspaper have different sets of expectations when reading the front cover than when they get to the comics. Even today’s movies are organized by comedy, drama, action, thriller, documentary, etc. To confuse an action movie, such as the film The Da Vinci Code, with a documentary, would lead to many thinking that all the details of the movie are truly factual.

Back to the Bible. I assume that most of my readers thus far would agree that the Bible has different genres. The problem is, most Christians don’t read the Bible as if it has more than one to distinguish. Rather, we tell ourselves that the Bible only has one single genre; a prophetic genre. We think that the Bible must, by necessity, have something in nearly every single passage that speaks to us as individuals directly in the year 2010. We call this by many names, such as personal application, or life meanings, or whatever. When we choose to ignore the distinctive features of genre found in the Bible, the text gets reduced to merely “What is it telling me today?”

One of my biggest pet peeves is people using Jeremiah 29:11 as a verse which God has for them as an individual. Most of you know it, or perhaps have heard it before, “For I know the plans that I have for you,’ declares the LORD, ‘plans for welfare and not for calamity to give you a future and a hope.” The problem is, this was written to the historical Jeremiah, not to me, or you, or your best friend. Some may feel threatened by my assumption, but if you don’t believe me, read the context. The previous two verses should be enough to show that this cannot refer to anyone in 2010, or 1999, or 300 C.E.

Let me be clear what I am not saying. I am not saying that God does not have a plan for you, or that you cannot use this verse for moral comfort. What I am saying is that this verse was written in a context, and that was to the prophet Jeremiah, not to me. It has a specific meaning for him and that should be given top priority.

Another example is the parable found at the beginning of Luke 16:1f, sometimes labeled the ‘Unrighteous Steward.’ I challenge anyone to try and read this with a 2010 application; I don’t think it can be done. It makes the best sense in the contexts of Jesus’ ministry as being told to his opponents. Again, the tendency to read it as prophetic for the year 2010 seems to miss the point.

Where am I going with this? My point is that if we simplify the Bible too far, we lose significant information and are in danger of accidently distorting what the original authors intended for their readers to hear and understand. Yes, the Bible has clear and specific points of application for all readers, such as the call to repentance and belief in the gospel. Yet the Bible also has context specific instructions, like the command to the Corinthians to greet one another with a holy kiss (does anyone still do this today?)

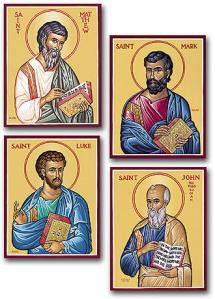

Scholars who are trained to recognize genre have a lot of help the church in this area. I recently have asked myself, “What is a Gospel?” I always assumed that they are histories, similar to what I read in US History in High School. Many scholars today have pinned the ancient Gospels found in the New Testament as Greco-Roman biographies, of which we have many others which survived from the same time period (over ten others). It seems that they are ancient biographies of Jesus shaped by resurrection faith and distinctives of the various four authors. I could say more on this, but I’d rather open things up for comments. Here are my questions to those who are still reading:

-Do you only read the Bible as if it had a personal meaning for you in every passage?

-Does recognizing genre and taking the various forms of it found within the pages of Scripture diminish the Bible in any way or does it enhance it? Why?