I had the privilege of attending last night’s debate on “Did Jesus Exist?” between two well-versed debaters – Dr. Craig Evans and Dr. Richard Carrier. When I learned of this debate, I wanted to take advantage of listening to Carrier, who is probably the world’s foremost mythicist scholar. In other words, I felt that this debate would expose me to the best arguments scholars could put forth suggesting Jesus was simply made up in history. Now I took plenty of apologetic classes in my undergraduate and graduate studies to become convinced of the overwhelming evidence regarding Jesus’ existence, but I could not pass up the chance to listen to Richard Carrier live. So I piled up my car with a few of my bright students and we took off to witness the debate.

I had the privilege of attending last night’s debate on “Did Jesus Exist?” between two well-versed debaters – Dr. Craig Evans and Dr. Richard Carrier. When I learned of this debate, I wanted to take advantage of listening to Carrier, who is probably the world’s foremost mythicist scholar. In other words, I felt that this debate would expose me to the best arguments scholars could put forth suggesting Jesus was simply made up in history. Now I took plenty of apologetic classes in my undergraduate and graduate studies to become convinced of the overwhelming evidence regarding Jesus’ existence, but I could not pass up the chance to listen to Richard Carrier live. So I piled up my car with a few of my bright students and we took off to witness the debate.

Here are some of my observations of last night’s event:

Evans’ Opening Statement

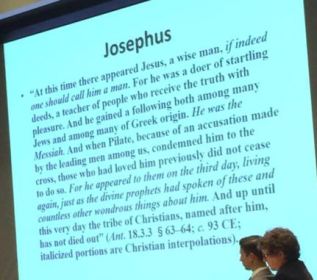

Craig Evans provided a well-rounded presentation with the typical Christian apologetic stance on Jesus’ existence. None of the arguments were new nor controversial. He noted that Paul and James (Jesus’ brother) were converted after the risen Jesus appeared to them.  Evans pointed out that Paul had conversed with Peter, one of the early disciples of Jesus. He also noted all of the early Greek and Latin authors who mentioned Jesus or who were aware of Jesus’ existence (Josephus, Tacitus, Pliny, Suetonius, Celcus, Lucian of Samosata, and Mara ben Serapion). Evans furthermore indicated that the four Gospels were written within a reasonable time from Jesus’ death to contain reliable information about him. I was actually impressed that Evans noted openly in his opening statement that the ‘Jesus passage’ in Josephus Antiquities 18 had indeed been doctored up by Christians. He gave this PowerPoint slide to note, in italics,

Evans pointed out that Paul had conversed with Peter, one of the early disciples of Jesus. He also noted all of the early Greek and Latin authors who mentioned Jesus or who were aware of Jesus’ existence (Josephus, Tacitus, Pliny, Suetonius, Celcus, Lucian of Samosata, and Mara ben Serapion). Evans furthermore indicated that the four Gospels were written within a reasonable time from Jesus’ death to contain reliable information about him. I was actually impressed that Evans noted openly in his opening statement that the ‘Jesus passage’ in Josephus Antiquities 18 had indeed been doctored up by Christians. He gave this PowerPoint slide to note, in italics,  which sections he felt were added. I applauded Evans for admitting this

which sections he felt were added. I applauded Evans for admitting this

honestly, although perhaps he was getting it on the table for discussion early, thinking that it would be heavily discussed (which it eventually was throughout the debate). All in all, Evans demonstrated that, at his age, he is sharp and well-versed in the Christian responses to historians and mythicists.

Carrier’s Opening Statement

Richard Carrier stuck me as a very eloquent speaker. He appeared very confident and was not afraid of being in the minority in regard to scholarship. I suppose taking a mythicist position requires you to develop thick skin. The first thing Carrier presented was basically that early Christianity was really no different than other pagan religions which honor a  dying and rising savior deity, albeit packaged into a Jewish form. I was struck at how he tended to take the position that if there was any possibility at explaining away the evidence for Jesus’ existence that it should be considered. Carrier did admit that it was plausible that Jesus historically existed, an admission which I found interesting coming from Carrier. I was disappointed that he dismissed the existence of Q, citing Mark Goodacre as one of the Christian scholars who does the same. Then things got interesting. Carrier suggested that Philo believed that an archangel was called ‘the firstborn son of God,’ the ‘image of God,’ and was depicted as God’s agent in creation in addition to being the celestial high priest. Then he cited Rom. 8:29; 2 Cor. 4:4; 1 Cor 8:6; and Heb. 4:14 to suggest that early Christians believed the very same things about Jesus. Of course there are different ways to interpret Jesus’ title of ‘firstborn’ and the meaning of 1 Cor. 8:6, but Carrier seemed adamant that his reading was the correct reading. He continued by noting that Mark, Matthew, and Luke, being the earliest Gospels, possessed a christology without preexistence. So far, so good (I thought). Then he suggested that these early Gospels had deliberately suppressed an early high christology of Paul, who, according to Carrier, believed and

dying and rising savior deity, albeit packaged into a Jewish form. I was struck at how he tended to take the position that if there was any possibility at explaining away the evidence for Jesus’ existence that it should be considered. Carrier did admit that it was plausible that Jesus historically existed, an admission which I found interesting coming from Carrier. I was disappointed that he dismissed the existence of Q, citing Mark Goodacre as one of the Christian scholars who does the same. Then things got interesting. Carrier suggested that Philo believed that an archangel was called ‘the firstborn son of God,’ the ‘image of God,’ and was depicted as God’s agent in creation in addition to being the celestial high priest. Then he cited Rom. 8:29; 2 Cor. 4:4; 1 Cor 8:6; and Heb. 4:14 to suggest that early Christians believed the very same things about Jesus. Of course there are different ways to interpret Jesus’ title of ‘firstborn’ and the meaning of 1 Cor. 8:6, but Carrier seemed adamant that his reading was the correct reading. He continued by noting that Mark, Matthew, and Luke, being the earliest Gospels, possessed a christology without preexistence. So far, so good (I thought). Then he suggested that these early Gospels had deliberately suppressed an early high christology of Paul, who, according to Carrier, believed and  taught that Jesus was an archangel who became incarnate in the human Jesus. He cited Phil. 2:5-11, which he repeatedly referred to throughout the debate, as the primary evidence for Jesus being a preexisting archangel (more on this later). He also suggested that angelos in Gal. 4:14 was best understood as an angel rather than a human messenger (as I would argue Paul intended). He then suggested that Jesus knew Moses according to 1 Cor. 10:4 (despite the fact that a few verses later Paul declared that he is speaking typologically). Carrier ended his opening statement by noting that early Christians spoke of resurrection appearances of Jesus in a way which he best felt are explained as ‘visions,’ visions which other pagan cults (ancient and modern) cite to validate their made up religious claims. In sum, Richard Carrier felt that Christianity is no different than other dying and rising savior deities in the ancient world.

taught that Jesus was an archangel who became incarnate in the human Jesus. He cited Phil. 2:5-11, which he repeatedly referred to throughout the debate, as the primary evidence for Jesus being a preexisting archangel (more on this later). He also suggested that angelos in Gal. 4:14 was best understood as an angel rather than a human messenger (as I would argue Paul intended). He then suggested that Jesus knew Moses according to 1 Cor. 10:4 (despite the fact that a few verses later Paul declared that he is speaking typologically). Carrier ended his opening statement by noting that early Christians spoke of resurrection appearances of Jesus in a way which he best felt are explained as ‘visions,’ visions which other pagan cults (ancient and modern) cite to validate their made up religious claims. In sum, Richard Carrier felt that Christianity is no different than other dying and rising savior deities in the ancient world.

Moderation

I was disappointed at the moderator of this debate, who seemed to be infatuated with the discussion taking place to the point of multiple times forgetting his moderating responsibilities. During the cross examination time, he never called Evans out when he spent three minutes making a rebuttal to Carrier which was not in the form of the question. Carrier was, however, polite and did not appear upset that the moderator was failing in his responsibilities. When it came time for audience Q&A, the moderator furthermore seemed unprepared of how the questions were to be asked and where the audience members were to form a line.

Audience Q&A

I do want to share the question which I asked both Carrier and Evans. I posed a challenge (at first to Carrier) that his argument regarding how the earliest christology was supposedly high, depicting Jesus as a former archangel according to Phil. 2:5-11. I read the Greek from Phil. 2:5-6a and asked what sense was Paul supposedly making to his Philippian converts if he expected them to “have this attitude among yourselves, which was also in Christ Jesus [Phil 2:5]” if Jesus used to be an archangel and, one day, decided to become a human? “How in the world,” I asked, “were Paul’s converts to imitate that attitude?”

Carrier responded to my question gracefully, but in a way which only proved my point of how Phil. 2:5-11 is to properly to be interpreted. Carrier admitted that Paul didn’t expect his audience to imitate Jesus becoming incarnate from an archangel, citing instead examples from Jesus’ human life which could realistically be modeled for Christian behavior. In sum, Carrier confusingly said that Paul argues in Phil. 2:5-11 that although Jesus was formerly an archangel, he does not expect his readers to “have this attitude among yourselves [Phil 2:5],” thus indicating that Paul commands something for his converts to do which he believes is impossible.

I grabbed the mic and asked Evans if he would mind responding. He told me rather casually that, “Well, I think he [Carrier] hit the nail right on the head.”

I rest my case.

I also wanted to share something funny which one of my students (Nathan) told me. During the scheduled break in the middle of the debate, Nathan was washing his hands in the bathroom and Carrier was washing his hands in the sink next to him. Nathan noted how short Carrier was and almost told him, “You are about the same height that the historical Jesus was – 5 foot 7!” But he didn’t. He told me afterwards and I laughed with him.

I still feel that the arguments for Jesus’ existence are strong and that Christianity is actually more different from the local cults of its times rather than being similar to them.